When I was in grad school, I played second trumpet in the faculty brass quintet. It was a nerve-racking situation, since all of the other musicians all had their doctorates in music

performance and had been teaching for many years, while I was a conducting major fresh out of undergrad. I took most of what they said and how they practiced as gospel truth.

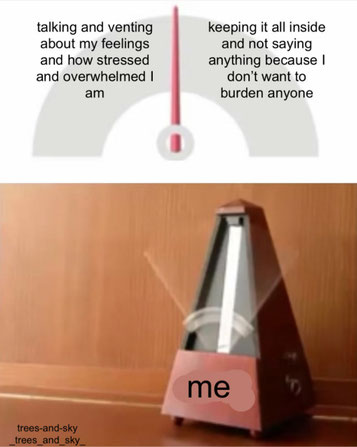

But one source of frustration for me was how often they wanted to play with a metronome. It was at least 95% of the time. They all seemed to agree that it was essential. But I

struggled—it seemed I could pay close attention to the metronome, or close attention to the other parts, but not to both, and the playing felt mechanical.

I did eventually learn to pay attention to both, and I will admit that I grew from the practice, but our performance tempo never matched our rehearsal tempo, and I always felt that we were less

responsive as a group because we had become slaves to the metronome.

It wasn’t until this year that I learned that my instincts were right! Studies of musicians brains show that practicing with a metronome is less effective than keeping good time on one’s

own, and that slavish devotion to the metronome can hurt performance.

So the question then becomes, how does one develop good time in the first place? The answer is—well, um—use a metronome.

Wait, what?

It turns out there are good ways and bad ways to use a metronome. Let’s unpack why, and it’ll give us some insight into how we can use it more effectively.

So why doesn’t the metronome bestow magical time-keeping powers? Well, the brain functions differently when it’s responsible for keeping its own time. A metronome, when used normally,

allows part of the brain to stop making that effort. And unfortunately, it turns out that the part of the brain that stops making effort is the exact same part of the brain that we need to

strengthen if we are going to play in time during performance.

Remember myelin production? It turns out to be important for keeping good time, too. In order to keep good time, we need to practice keeping good time (I know that sounds like a “duh”

statement, but too often we let the metronome do it for us).

So what we need is, on the one hand, a way to tell if we’re keeping good time (the metronome’s job) and on the other hand, a way to keep using the part of the brain that shuts off when we use the

metronome. Aren’t these mutually exclusive?

Luckily, there’s an easy solution, which is to use the metronome, but not for every beat. You can set it to click every 2, 3, 4, or more beats, depending on the meter and how stable your

time is. Then extend it out to multiple measures, so it’s clicking every 8 beats (for 2 measures of 4/4, for example) or 12 or 16. You’ll quickly notice places where your time isn’t

quite what you thought it was, and those are good areas to focus on with the metronome.

Slavishly following the dictates of the metronome still has a place in good practice, of course. When you are still working up a section of music, particularly a technically or rhythmically

difficult passage, it’s a good idea to use every beat of the metronome to help smooth out the difficulties. In fact, you are working on two different skills, both of which have different

myelin pathways in the brain. Skill number one is the physical technique, which can be greatly aided by an external crutch like the metronome. Skill number two is keeping good time,

and that’s the skill that requires you to use the metronome as a check-in on your own skill rather than using it as the timekeeper.

The larger point here, as in my article about tuners and drones, is that we need to closely discern what skill we’re practicing (technique or timekeeping? tuning or listening?), so that we choose

the right tools and challenges to stretch ourselves productively.

Write a comment